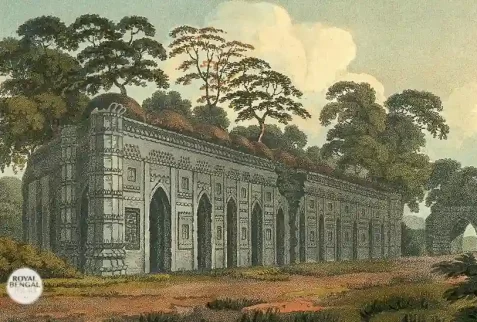

It derived its name from the fact the original roofing with fifteen gilded domes, including Chau-Chala (Bengal- Hut-Style) domes in the middle row. The inscription found on the front wall indicates that the Mosque was built by Majlis Mansur Wali Muhammad bin Ali sometime between this period 1493 -1519 AD.

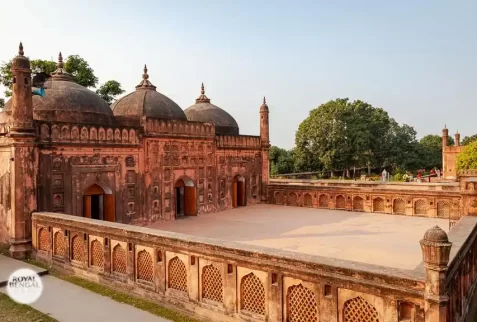

The rectangle shape mosque is made from bricks and stones. This elegant monument has a gently curved cornice characteristic of the era and has stone channels to drain out the rainwater from the roof. All four external walls and, to some extent, internal walls are covered with granite stone blocks. The Mosque originally was surrounded by 42m (East to west) and 43m (North to south), an outer wall with a gateway in the middle of the eastern side. Except for the gateway, the entire surrounding wall has disappeared, but it can be traced from the remains.

There is an ornate’ Ladies Gallery’ or Badshah-ka-takht carried on finally carved slender stone columns in the northwest corner of the Mosque.

The superb decoration is the main attraction of this monument. Carved in shallow relief on both the outer and inner surface of all walls, the elaborate stonework seems like a faithful replication of the extremely developed typical terracotta arts of Bengal, and it is the similar appearance that is found in its wood- carvings or filigree work. The inner floor of the Mosque was originally covered with decorative shiny tiles with floral patterns.

On the southeast corner of the mosque premise is two modern graves of the then Heroic East Pakistan Military Soldiers Major Nazmul Hoque Tulu (d 27 September 1971) and Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir (d 14 December 1971), who died near Chapai Nawabganj Town during the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971, fighting against the Pakistani Army.